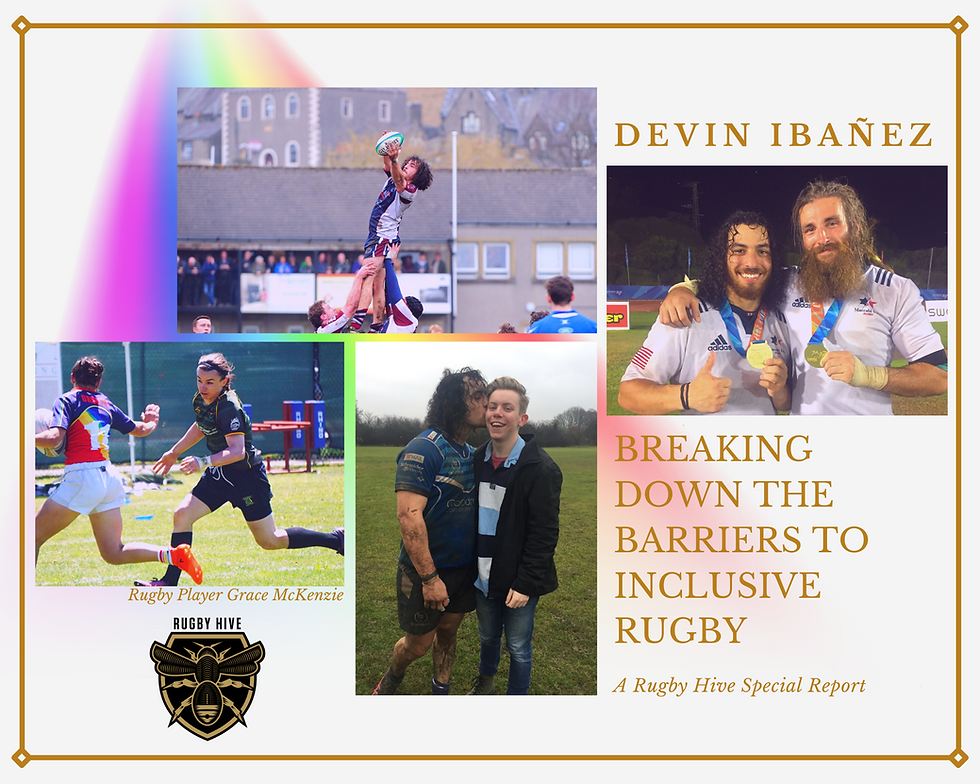

Devin Ibañez – Breaking Down the Barriers to Inclusive Rugby

- Karen Gasbarino

- Jun 9, 2021

- 10 min read

27-year-old Devin Ibañez was one of the first signees for the New England Free Jacks for their exhibition season, a true moment of hometown pride for the Boston area native. The big flanker played for the Free Jacks through the 2019 season but then was sidelined with injury, followed by the premature end to the 2020 season due to the global pandemic.

Ibañez has played since he was 15 years old. He played at high school, University, the local level, and has represented the USA at the Maccabiah games. His goal is to captain his team at the games in 2022.

Off the pitch, Ibañez has been openly gay to those close to him since he was a teen, but he came out to the rest of the world at the end of 2020. It was a decision he’d been discerning seriously for years. But with COVID-19 preventing him from being with his partner Fergus – coupled with the nagging feeling that the time was right, right now – Ibañez created the IG profile @thatgayrugger. It was mostly to surprise Fergus, but also to acknowledge his sexual identity to the world. And while the motive wasn’t initially to attract attention (going so far as to turn off notifications on the initial post) the support started to come through and he soon realized that he was a game changer.

Following a forced separation greater than a year, Ibañez has finally reunited with Fergus in the UK and is playing for Richmond RFC in the London area. He’s working through the mainly positive aftermath of his announcement, talking a fair amount to the press, and finding what he considers a surprising amount of support for his decision.

Part of the support he’s felt came from his former team. Ibañez spoke to our own Dallen Stanford in March of this year on the New England Free Jacks Live Show about the encouragement he’s received.

The plan for Ibañez has always been to come out and then continue to play rugby professionally, offering a beacon of hope to others who live in the headspace he was living in only six months ago. In the meantime, living true to himself offers palpable relief.

It also affords him the opportunity to speak to the issue of inclusion that our sport faces.

Ibañez has always supported issues affecting the LGBTQ+ community as his sister has long been an advocate within the group; Devin feels he has learned a lot about the issues facing transgender people. In particular, the representation and decisions affecting the LGBTQ+ sporting community. Of note, the 2020 ruling of World Rugby to prevent transgender athletes from competing at the highest level.

Living true to one’s self is paramount to Ibañez. Supporting those trying to live by the same code comes naturally. “After I came out, I realized that I was in this position to use my voice and speak out in a way that others haven’t,” Ibañez says of the issue to ban trans women from competing internationally. He adds that it’s an issue most professional players steer well clear of. It’s a very divisive subject.

Before we go any further, I’m putting my hand up.

I believed that the widely shared concerns about transgender athletes in elite sport were founded on fact. I believed, along with many, that more research was needed.

Along with a lot of other rugby supporters not equipped with all the pertinent information (aka both sides of the story) I bought into the rhetoric about allowing transgender women to play rugby alongside and against other women, about the physicality of the game and the size of the players, about the increased danger to all players, and about the so-called advantage to any team with transgender players on it. I believed my caution could be attributed to the issue of safety for all players, especially cisgender players – those who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth.

But I was wrong.

Saying ‘we need to look into this further’, as World Rugby has, is largely side-stepping and prolonging the need to have a long look in the mirror. Is it really all about player safety? It is, after all, highly controversial. World Rugby would need to present an unwavering and firm stance in the face of what is such an incredibly divisive issue.

Collectively, we have shied away from what is likely the most contentious subject World Rugby has ever faced. But the time has come for us to face it head-on and to tackle the MANY falsehoods about transgender players.

“There’s this whole group of people supporting World Rugby’s decision who don’t have the full picture and context of not only the reality of trans athletes in rugby but also of how harmful the rhetoric really is, and how many people it’s going to push away from a space which has been so inclusive for them for so many years,” Ibañez says. He adds that being included in sport offers a safe haven for trans athletes. The announcement has them feeling as if the rug has been pulled out.

The pivotal shift for me occurred when I tuned in to an Instagram ‘live’ Ibañez hosted. His guest was the incredibly well-spoken transgender rugby player Grace McKenzie. They spent an hour breaking down the issue.

I was riveted. Both spoke unwaveringly. They know their subject and they know the facts, which they presented with clarity and in the spirit of education; there was no preaching, no emotion, no anger. It was just, ‘listen folks, World Rugby has got it wrong, we’ve got to look at this again.’

At issue: Player safety. Ibañez asks, “do women rugby players actually feel like there’s an issue of safety? Do they really feel like they are at a competitive disadvantage? The overwhelming answer to that is that they don’t. But did anyone ask them?” Further, did anyone talk to any trans players about the issues? Or about their responsibility as a teammate? Ibañez says these conversations haven’t happened. Yet they need to.

“It’s been made into an issue of legal liability,” Ibañez says. “But there’s just no merit to it. It comes back to the same thing. There is no evidence of higher injury risk from including trans women. There is no documentation of there being some significant danger trans women are putting their teammates and opponents under.” The vast majority of trans athletes are just looking for the opportunity to compete, to be included, to be part of a team.

By barring trans women from the highest level, Ibañez worries that a domino effect will be put in motion. “People say ‘well okay at least they’re still allowed to participate at other levels of the sport’. But it’s setting this precedent that begs the question of 'how long is it before they’re banned from other levels of the sport as well?'”

He continues: “If the best players in the world who have the best training and the best technique, the best tackling ability, strength, fitness, and all that are NOW considered NOT strong enough or good enough to play against trans women, how long is it before the same assessment is made of every single level of rugby?” A tough question. And a poignant statement.

DALLEN & ROBIN SPEAK TO TRUE RUGBY LEGENDS ON THE RUGBY HIVE PODCAST

The most eye-opening fact which made me realize my misgivings were unfounded is that there are already requirements in place for trans players. A woman in transition cannot participate in rugby at any level, with or against other women until she has been on estrogen-based hormones for a specified period of time. I’ll elaborate shortly – but suffice to say that a lot of people are simply not aware of the regulations. Yet they do exist.

Grace shared that during her transition, she lost strength and speed the longer she was on hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The more testosterone that was replaced with estrogen, the more Grace was physically and physiologically becoming a woman. She’s still fit and continues to train, but it’s basic body chemistry; she isn’t even the fastest, strongest, or tallest woman on her rugby team in San Francisco.

Hearing about how the transition actually works versus how we imagine it working was so illuminating for me. On a basic level, how many of us make the mistaken assumption that transgender players are women on the outside but men on the inside, still as fast and as hard as their male counterparts? Ibañez agrees that people tend to get the most dominant trans athlete image in their head, and with broad strokes make their false assumptions.

World Rugby is the first international sport-governing body to ban transgender women athletes from international women's competition. In their explanation, World Rugby offered that they had “concluded that safety and fairness cannot presently be assured for women competing against trans women in contact rugby.” However, they are happy to offer the caveat that transgender women can still participate in rugby – at the local level.

So, you can play, you can train, you can put in the hard graft, and put your body on the line. Just not for your country. Grace, and many women like her, were left completely deflated by the decision.

But it’s also deeper than that. This is where the domino effect kicks in. Ibañez explains: “Will you pick a trans player for a youth select side? Would you give them those opportunities if they are going to hit a wall where they can advance no further?” He asks if anyone would invest in a player they can only go so far with. His worry, shared by the trans community, is that coaches will not want to put time and resources – already limited in many markets – into such players.

Not all is lost, which is why this is a conversation that has to happen now, and not once it’s too late. Certain national bodies, including USA Rugby and Rugby Canada, have rejected World Rugby’s decision. This is a step in the right direction. But more needs to be done.

On the one side are those who suggest that safety concerns must take precedence and suggest that transgender women have gained some vague “physical benefits” from having gone through male puberty. While this is the argument which many support, it’s really only half the story, and as McKenzie states "a poor understanding of the reality of the biology of trans women undergoing HRT." How many studies have been done on trans women athletes both before and then well after their transition? I couldn’t find any.

There is the possibility a team could be accused of having an unfair advantage for including a transgender player on their roster. Yet, on any given match day at any level, someone is bound to feel the game wasn’t “fair”. Consider some forward pack weights with a 50 or even 100 kg advantage over their opponents, a missed call, teams disagreeing with officiation. There are often issues supporters will champion in defence of their own team.

As with any other player who has gone through the ranks, a transgender player has to be good enough to make it all the way to the top. They’ve got to rise above local and regional levels before being selected to a national training side. They have to be a leader on and off the pitch, a total team player. These are big asks for all elite athletes, many of whom don’t make it to the top for a myriad of reasons. The playing ground is much fairer than detractors think.

The discernment process a person undergoes in order to arrive at the decision to transition is lengthy, before the physical change is even undertaken. In all probability, the decision has been weighing heavily on the individual for years, often since puberty, and sometimes even before. The person’s sport is only a small part of the whole, and it is so often what grounds them during what must be a turbulent time.

A friend of mine Alexandra Kemp offers a glimpse into the timeline regarding hormone replacement therapies. She shares that taking HRT (hormone replacement) is a lifelong commitment. Most transitions are “probably two to three years at least, since most of the time, you want to be on HRT for two plus years before any surgeries so you can see how your body will ‘naturally’ adapt.” It’s a commitment which requires management.

Kemp adds that it makes perfect sense for professional sport to have a requisite for trans women to achieve before they can compete.

She says, “it’s normally X amount of time on HRT, or Y amount of testosterone when undergoing a blood test, or a combination of both.” The new guidelines set forth by the IOC (International Olympic Committee) are that a trans woman athlete declares their gender and not change that assertion for four years, as well as demonstrate a testosterone level of less than 10 nanomoles per liter for at least one year prior to competition and throughout the period of eligibility. Levels would continue to be monitored, much in the way we check for performance-enhancing drugs.

As a woman in the midst of transition, Kemp adds “I actually personally agree with these guidelines, as it’s the testosterone and the muscle mass it produces that would give us [individuals who went through puberty as male] an advantage, so you want a trans woman to have enough time without naturally high testosterone levels in order to keep competitive parity.” This echoes what McKenzie and Ibañez discussed in their IG live.

With the technical aspects of transition explained, and the safety issues dispelled, it all boils down to inclusion.

Ibañez says he believes, as many of us do, that rugby IS the most inclusive sport. He wants rugby to stand by their own ethos. Inclusion isn’t just about sexuality, gender, or racial diversity.

To Ibañez, they are intricately connected. He says, “all these issues are naturally linked because inclusion in sport, inclusion in rugby, and having an inclusive environment isn’t about gearing that environment to be inclusive to one person. It’s not about making your team gay friendly or trans friendly or diverse to all different backgrounds and races. It’s about being holistically inclusive and celebrating diversity.

“How can we make the sport one that feels welcome to everyone? For the longest time we have said that there is a place for everyone in rugby. So, what are we doing to make sure that message is reciprocated in a training environment?”

It is said time and again that rugby is different from other sports. We support each other’s mental health. We embrace different body shapes and abilities.

I think it’s okay for us to admit we have approached this issue on the wrong foot. There is still time for a course correction.

Let’s stand behind Ibañez, McKenzie, and all the players who need our support. Let’s continue the conversation. So that trans players continue to feel that rugby is their safe haven.

To learn more:

A piece about Grace McKenzie’s journey: Transgender ban a 'dangerous precedent'

France votes unanimously in favour of allowing transgender women to play: Transgender Women to Play in France

Ibañez also further lays out the issue with incredibly clarity in his op-ed piece available on his website thatgayrugger.com. I urge you to have a read.

Karen L. Gasbarino, June, 2021

Rugby Hive Editor

Listen to the Rugby Hive Podcast and connect with us on all the socials:

Comments